Friday Tidbits #6: Alcohol, Sleep, Zinc and HRV

Welcome to Friday Tidbits. This is a very short email with morsels of information to help you tweak your life and health for optimum longevity and healthy ageing.

8 Dec 2023

Sleep

Alcohol sedates you out of wakefulness, but it does not induce natural sleep - Matthew Walker in Why We Sleep.

Drinking alcohol 1-3 hours before bed makes you fall asleep faster, increases NREM sleep but decreases REM sleep during the first half of the night (1). During the second half, wakeful episodes increase and REM sleep “rebounds”. In other words: alcohol fragments sleep, it induces frequent light awakenings, severely compromise healthy sleep architecture. Your sleep is less restorative. Even if you drink alcohol late afternoon (6 hours before bed) your sleep is disrupted.

Alcohol inhibits the excitatory activity of the glutamate NMDA receptor in brain cells. Watch this 2-minute video explaining brain cell communication through neurotransmitter signalling. Glutamate functions as an excitatory neurotransmitter and when glutamate signalling is blocked at the NMDA receptor, electrical activity is reduced. Alcohol depress brain function in the same style of an anaesthetic (2) and benzodiazepines (3). In effect, alcohol induces unconsciousness not natural sleep (3).

Figure 1: Normal sleep architecture showing the stages of sleep and the relative contribution in each cycle. Deep sleep (NREM3 & 4) make up most of the cycle during the first half of the night with only a few minutes in REM. In the later part of the night this is reversed. From Aliakseyeu et. al 2011 (4)

HELP is at hand ;)

Alcohol metabolism relies on a 2-step enzymatic process. The enzymes, alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH), require zinc and vitamin B3 (as NAD+) to function. Make sure you ingest additional zinc and B-vitamins in your diet when you know you are going to consume alcohol. The supplement Recoverthol, contains these cofactors to help metabolise alcohol. I have not used it, but the logic seems sound. If I were to create a product to help with alcohol metabolism is would contain zinc, vitamin B3 or nicotinamide riboside (NR), all the other B-vitamins and NAC as a precursor to glutathione.

Nutrition

Low dietary zinc intake lower thyroid hormone levels which in turn can lower basal metabolic rate (BMR).

In 1986 (5), six healthy young men took part in a small metabolic ward study lasting 75 days. They received a diet with a zinc intake of 5mg/d. The recommended daily intake (RDI) for zinc is adults are 14mg/d for males and 8mg/d for females. Thyroid hormones (TSH, T4 and fT4) and BMR decreased during the period and returned to normal when adequate zinc was fed. More recently, zinc supplementation of 26mg/d, improved thyroid levels and BMR of two zinc deficient female athletes in four months (6).

Thyroid hormones play a big role in the regulation of energy metabolism. People with hypothyroidism (too levels of thyroid hormones) typically experience lower energy levels, fatigue, low tolerance for exercise and performance and struggle to lose weight.

Zinc is involved in over 300 enzymes including those involved in energy metabolism and the immune system. Zinc forms part of the 1,5’-deiodinase enzyme that converts the inactive T3 into the active form T4.

The optimum range for plasma zinc is 100-120 mcg/dL or 10-12 umol/L.

Oysters are the best source of zinc with ~30mg per 100g. The zinc in animal food source, red meat, fish, chicken and dairy are more bioavailable than plant foods. Plant sources high in zinc include fortified cereals, oats and pumpkin seeds.

Note: zinc and iron compete for absorption in the gut. Supplementing with high levels of one may induce deficiency of the other(6).

Movement

Social ballroom dancing improve balance, mobility and executive function in dementia-at-risk older adults similar to traditional treadmill walking.

The randomised clinical trial was conducted over 6 months with 25 adults, older >65y identified with mild cognitive decline scores (7). Participants were allocated to 90min twice per week social ballroom dancing or treadmill walking. Executive function improved in both intervention arms. The digit symbol substitution test (DSST) change was significantly greater in the dancing group. Executive function was evaluated using a composite from DSST, flanker interference and walking while talking tasks

Executive functions such as planning, reasoning, problem-solving, organisation, attention allocation and inhibiting appropriate actions decline in ageing. These function are impaired in people with mild cognitive impairment, including Alzheimers Disease. Aerobic exercise improve neuroplasticity and executive functions but adherence to programs are low.

Dancing is a safe and effective activity that is aerobically demanding and also cognitively stimulating. And it increase social connection and interaction.

Stress & Breathing

Alternate nostril breathing can help calm your nervous system, ease your anxiety and improve your thinking.

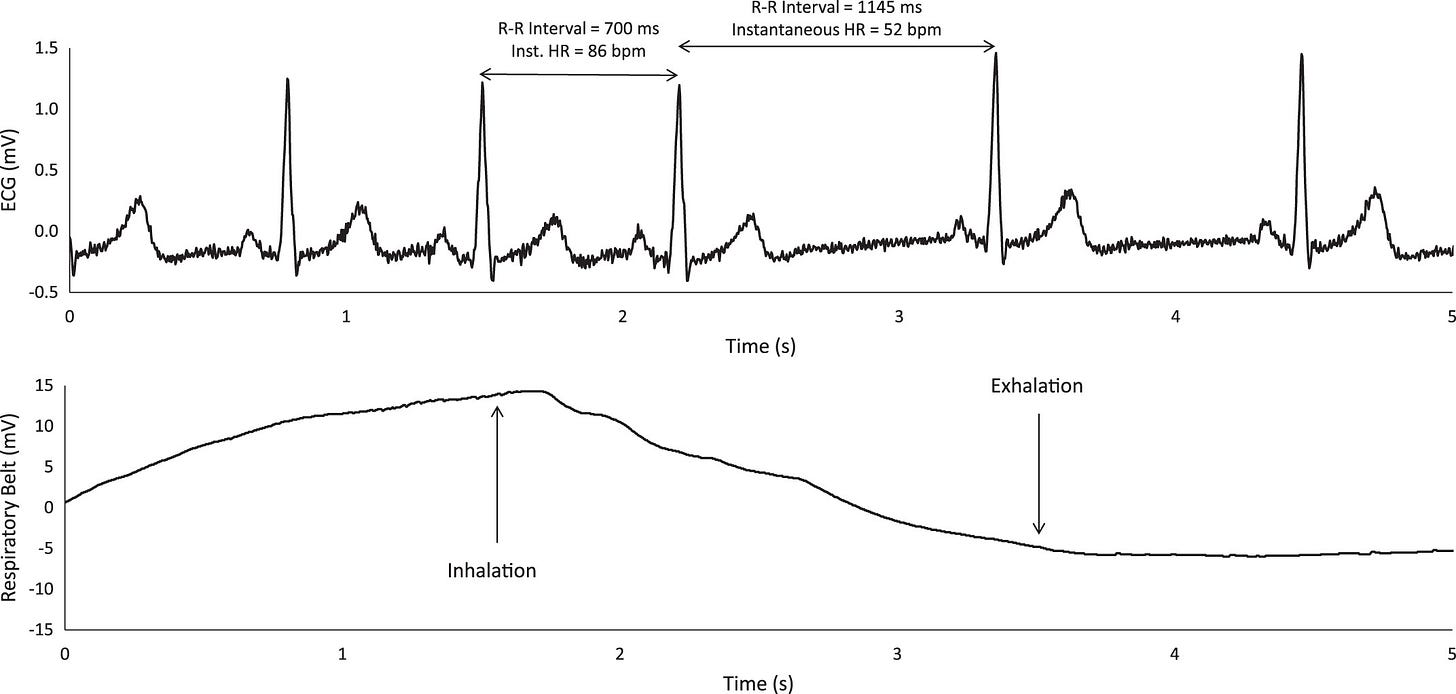

Heart rate variability (HRV) is a measure of autonomic function - how stressed or relaxed you are. Simplistically, HRV is the time difference between consecutive heart beats. The time between beats measured in seconds may be 1.00, 0.97, 1.03 and so on. A low HRV means the difference is very similar: 1.00, 1.01, 0.99. While a high HRV means the difference is larger between beats: 1.00, 0.93, 1.07 etc. A low HRV score is indicative of high levels of stress and poor recovery. The time difference is larger with exhales compared to inhales.

Figure 2. An ECG and respiratory tracing for an individual deep breath. These tracings from the ECG setup and respiratory belt illustrate the shorter R-R interval, and our own calculated instantaneous heart rate (HR) during inhalation and the protracted R-R interval and slower instantaneous HR during exhalation. bpm, Beats/min. From Levin & Swoap 2019 (9).

A higher HRV indicates that the parasympathetic (rest & digest) part of the autonomic nervous system has a higher influence over bodily functions compared to the sympathetic (fight & flight) part. The two parts of the autonomic nervous system work in concert to keep body functions in balance. When you are reading for pleasure, the parasympathetic arm has a higher tone. When you exercise, the sympathetic arm helps you move and react fast. The vagus nerve is the predominant influence for the rest and digest state.

Many breathing exercises will help improve HRV scores. Generally, any practice that focus on longer exhales will improve HRV. Slow breathing improve the cardio-vagal baroreflex sensitivity (8)(9). Slow breathing at 6 breaths per minute increased HRV with 5 min of daily practice (8). In a small study of 25 young males, the HRV scores improved after 6 weeks of performing 5 minutes of alternate nostril breathing per day (10).

The effect of alternate nostril breathing on acute stress was evaluated on students. The students were tasked to perform a 5 minute public speaking exercise after 15 minutes of alternate nostril breathing or sitting quietly. The group that performed the breathing exercise before the speech reported lower anxiety compared to the control group (11).

Note: many of the published research on alternate nostril breathing use small groups. Most of them are conducted in India were yoga philosophy and practice is very common and hence it is difficult to control for the sole effect of the breathing exercise.

Reference:

Knapp, Clifford M et al. “Mechanisms underlying sleep-wake disturbances in alcoholism: focus on the cholinergic pedunculopontine tegmentum.” Behavioural brain research vol. 274 (2014): 291-301. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2014.08.029

Banerjee, Niladri. “Neurotransmitters in alcoholism: A review of neurobiological and genetic studies.” Indian journal of human genetics vol. 20,1 (2014): 20-31. doi:10.4103/0971-6866.132750

Jones, Barbara E. “Arousal and sleep circuits.” Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology vol. 45,1 (2020): 6-20. doi:10.1038/s41386-019-0444-2

Aliakseyeu, D., Du, J., Zwartkruis-Pelgrim, E., Subramanian, S. (2011). Exploring Interaction Strategies in the Context of Sleep. In: Campos, P., Graham, N., Jorge, J., Nunes, N., Palanque, P., Winckler, M. (eds) Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2011. INTERACT 2011. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol 6948. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-23765-2_2

Wada, L, and J C King. “Effect of low zinc intakes on basal metabolic rate, thyroid hormones and protein utilization in adult men.” The Journal of nutrition vol. 116,6 (1986): 1045-53. doi:10.1093/jn/116.6.1045

Christy Maxwell, Stella Lucia Volpe; Effect of Zinc Supplementation on Thyroid Hormone Function: A Case Study of Two College Females. Ann Nutr Metab 1 June 2007; 51 (2): 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1159/000103324

Blumen, Helena M et al. “Randomized Controlled Trial of Social Ballroom Dancing and Treadmill Walking: Preliminary Findings on Executive Function and Neuroplasticity From Dementia-at-Risk Older Adults.” Journal of aging and physical activity vol. 31,4 589-599. 14 Dec. 2022, doi:10.1123/japa.2022-0176

Bhagat, Om Lata et al. “Acute effects on cardiovascular oscillations during controlled slow yogic breathing.” The Indian journal of medical research vol. 145,4 (2017): 503-512. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_830_15

Levin, C. J., & Swoap, S. J. (2019). The impact of deep breathing and alternate nostril breathing on heart rate variability: a human physiology laboratory. Adv Physiol Educ, 43(3), 270-276. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00019.2019

Sinha, Anant Narayan et al. “Assessment of the effects of pranayama/alternate nostril breathing on the parasympathetic nervous system in young adults.” Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR vol. 7,5 (2013): 821-3. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2013/4750.2948

Kamath, A., Urval, R. P., & Shenoy, A. K. (2017). Effect of Alternate Nostril Breathing Exercise on Experimentally Induced Anxiety in Healthy Volunteers Using the Simulated Public Speaking Model: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Study. Biomed Res Int, 2017, 2450670. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2450670